Theme Issue 53

History and Theory in a Global Frame

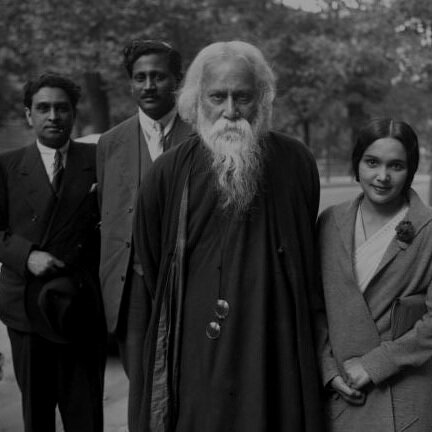

Cover image: photograph of Rabindranath Tagore in Germany, May 1931, from German Federal Archive (Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-11643).

+ ETHAN KLEINBERG and WILLIAM R. PINCH, History and Theory in a Global Frame, History and Theory, Theme Issue 53 (December 2015), 1-4.

No abstract.

+ NILS RIECKEN, History, Time, and Temporality in a Global Frame: Abdallah Laroui’s Historical Epistemology of History, History and Theory, Theme Issue 53 (December 2015), 5-26.

In this essay I discuss key elements of an original and hitherto neglected contribution by the Moroccan historian, intellectual, and theorist Abdallah Laroui to historical theory in a global frame: his historical epistemology of history and his theory of time and temporalities. I argue that Laroui develops a relational and dialectical form of translation that allows for translating between multiple forms of representing history and time. His attention to temporal logics across different bodies of historical thought enables him to translate concepts of history and time across putatively given “cultural” differences of “Western,” “Islamic,” and “Muslim” forms of historical thought. By unraveling these representations of difference as situated representations of time, he usefully historicizes the very conditions of observing historical difference. Besides outlining Laroui’s approach, which I characterize as a situated universalism, I trace how his outlook on historical theory is shaped by his particular location in a postcolonial Muslim society and in a complex relation to “the modern West.” Laroui understands his own location in postcolonial Morocco in dialectical terms as characterized by the interdependence of the local and the global, the indigenous and the exogenous, and the particular and the universal. It is his confrontation with multiple bodies of historical thought that pushes him toward a concern with problems of location, positionality, conceptual translation, and self-reflexivity leading to his engagement with epistemic frames and situated temporalities. Crucially, his epistemology of history and his theory of time and temporalities constitute a powerful critique of the temporal presuppositions of centrist views of history and time as self-contained beyond the Moroccan context. Laroui’s situated universalism, I conclude, helps to rethink the problem of historical difference beyond the limits of centrist accounts and within a global frame.

+ MARK THURNER, Historical Theory through a Peruvian Looking Glass, History and Theory, Theme Issue 53 (December 2015), 27-45.

In this article for the theme issue on “Historical Theory in a Global Frame,” I argue that “Peru” is a “historical theory in a global frame.” The theory or, as I prefer, theoretical event, named Peru was born global in an early colonial “abyss of history” and elaborated in the writings of colonial and postcolonial Peruvian historians. I suggest that the looking glass held up by Peruvian historiography is of great potential significance for historical theory at large, since it is a two-way passageway between the ancient and the modern, the Old World and the New, the East and the West. This slippery passageway enabled some Peruvian historians to move stealthily along the bloody cutting-edge of global history, at times anticipating and at others debunking well-known developments in “European” historical theory. Today, a reconnaissance of Peruvian history’s inner recesses may pay dividends for a historical theory that would return to its colonial and global origins.

+ XUPENG ZHANG, In and Out of the West: On the Past, Present, and Future of Chinese Historical Theory, History and Theory, Theme Issue 53 (December 2015), 46-63.

In ancient China, dissatisfaction with the official compilation of histories gave rise, in time, to reflections on what makes a good historian, as well as on such issues as the factuality and objectivity of history-writing, the relationship between rhetoric and reality, and the value of historians’ subjectivity. From these reflections arose a unique set of historiographical concepts. With the coming of modern times, the urgent task of building a nation-state forced Chinese historians to borrow heavily from Western historical theories in their effort to construct a new history compatible with modernity. A tension thus arose between Western theory and Chinese history. The newly founded People’s Republic embraced the materialist conception of history as the authoritative guideline for historical studies, which increased the tension. The decline of the materialist conception of history in the period since China’s reform and opening up in the late 1970s and, with this development, the increasing plurality of theories, have not exactly lessened Chinese historians’ keenly felt anxiety when they confront Western theories. For Chinese historians, the current state of affairs with respect to theory is not exactly an extension of Western theories, nor is it a regression to the particularity of Chinese history completely outside the Western compass. Rather, a certain hybridity with respect to theory provides to Chinese historians a way to move both in and out of the West, as well as an opportunity for them to make their own contributions to Western history on the basis of borrowed Western theories.

+ DILIP M. MENON, Writing History in Colonial Times: Polemic and the Recovery of Self in Late Nineteenth-Century South India, History and Theory, Theme Issue 53 (December 2015), 64-83.

This essay looks at two early texts by a Hindu religious figure, Chattampi Svamikal (1853–1924), from Kerala, the southwestern region of India. Kristumatachhedanam (1890) [A Refutation of Christianity] and Pracina Malayalam (1899) [The Ancient Malayalam Region] draw upon a variety of sources across space and time: the echoes of contemporary debates across India and Empire as much as the detritus of the Enlightenment contest between rationalism and religion in Europe. Does the location of the text in “colonial India” exhaust the space-time of its imagination? The essay argues for a porous rather than a hermetic understanding; the “text” was a supplement to the actual verbal confrontation on street corners and arguments in ephemeral print. The real question is how can historians write postnational histories of thinking? How should we engage with times other than the putatively regnant homogeneous, empty time of empire or nation? I argue that there is an immanent time in texts (arising from the conventions and protocols of the form, the predilections of the thinker, and imagined affinities with ideas coming from other times and places) that exceeds the historical time of the text.

+ MATEUS HENRIQUE DE FARIA PEREIRA, PEDRO AFONSO CRISTOVAO DOES SANTOS, and THIAGO LIMA NICODEMO, Brazilian Historical Writing in Global Perspective: On the Emergence of the Concept of "Historiography," History and Theory, Theme Issue 53 (December 2015), 84-104.

This article assesses the meanings of the term “historiography” in Brazilian historiography from the late nineteenth century to circa 1950, suggesting that its use plays an essential role in the process of the disciplinarization and legitimation of history as a discipline. The global-scale comparison, taking into consideration occurrences of the term in German, Spanish, and French, reveals that use of the term took place simultaneously worldwide. The term “historiography” underwent a significant change globally, having become independent from the modern concept of history, shifting away from the political and social dimensions of the writing of history in the nineteenth century and unfolding into a metacritical concept. Such a process enables historians to technically distinguish at least three semantic modulations of the term: 1. history as a living experience; 2. the writing or narration of history; and 3. the critical study of historical narratives. Based on the Brazilian experience, it is possible to think of the “historiography” category as an index of the transformations of the modern concept of history itself between the 1870s and 1940s, a period of intense modification of the experience and expectations of the writing of professional historical scholarship on a global scale.

+ CHRISTOPHER CLEMENTS, Between Affect and History: Sovereignty and Ordinary Life at Akwesasne, 1929–1942, History and Theory, Theme Issue 53 (December 2015), 105-124.

This essay seeks to recover the ordinary and its analytical and decolonial potential within the extraordinary conditions created by settler colonialism. To do so, it investigates moments when Mohawks at Akwesasne, a community that straddles the US–Canada border, refused to acknowledge settler authority, paying particular attention to the relationship between their refusals and the condition of ordinary life. This article also considers the historical challenge of how to preserve moments of experience and their complex meanings without enveloping them in broader narratives dominated, in this case, by questions of sovereignty. How do theories of sovereignty affect the production of history, and what constraints do they place on our ability to narrate Indigenous experiences? What if we cast away the two narratives that dominate tellings of Indigenous histories: that of a settler crisis over control and that of an age-old struggle for sovereignty? Is it possible, or useful, to differentiate between acts focused primarily on maintaining the contours of ordinary, everyday life—expressions of lateral agency less about the “long haul” than about the here-and-now—and deliberate acts of political engagement, consciously aimed at the structural inequality undergirding a particular situation? Through a deep historical treatment of several moments within Akwesasne’s early twentieth-century history, this essay proposes and attempts to execute a methodology that draws together multiple theories of affect and sovereignty.

+ RANJAN GHOSH, Rabindranath and Rabindranath Tagore: Home, World, History, History and Theory, Theme Issue 53 (December 2015), 125-148.

This article, through a close reading of Rabindranath Tagore’s writings on history, tries to develop his theory of history and establish the character of his historical consciousness. Tagore’s philosophy of history is distinguished from Western models of historical thinking and is resistant to aligning with nationalist and revivalistic narratives that speak only of one culture, one nation, and one community. The article works out a theoretical premise based on Tagore’s engagement with time, historical distance, the everyday, history as life-view, historical fiction, historicality in literature, and the notion of the historical-now or presentism. Substantiated by the notion of a “poet-historian,” Tagore’s historical theory works at the limits of “global history,” which is now often misappropriated through the principles of unifocality and bounded rationality. The article develops Tagore’s sense of itihasa that frees history from the univocality of world history, creates its own “worlding,” its historicality, enriching and disturbing our notions of global history.